I'm a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellow at the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Oxford, and a Junior Research Fellow at Wolfson College, Oxford. I defended my PhD at the Caltech Seismolab in October 2021. I'm passionate about inverse problems and cutting edge applied mathematics — some of the projects I'm working on now are: accelerating seismic wavefield simulations with machine learning, imaging the Earth from near surface to the core; improving data captured at seismic arrays; and studying the time-varying behaviour of seismic swarms.

You can contact me at jack.muir@earth.ox.ac.uk

TerraPINN: Toward fully physics based probabilistic seismic hazard assessment using physics informed neural networks

With Tarje Nissen-Meyer at Oxford, I am investigating the recently developed physics informed neural networks (PINN) methodology to accelerate synthetic seismic wavefield propagation. PINNs learn to solve physical problems with little or no labelled training data. Instead of using data, they seek to minimize their physics error. PINNs may potentially offer a way to provide very fast approximate solutions to partial differential equations. Preliminary results have been promising, but scaling PINNs to large, multiscale problems has been challenging. I'm investigating a hybrid approach - first, reduce the dimensionality of the problem by fitting synthetic data via traditional machine learning in a plane containing the source, and then expand that plane to 3D using PINNs. Our initial application will be to incorporating realistic wavefield propagation effects into physics based probabilistic seismic hazard (PSHA) workflows.

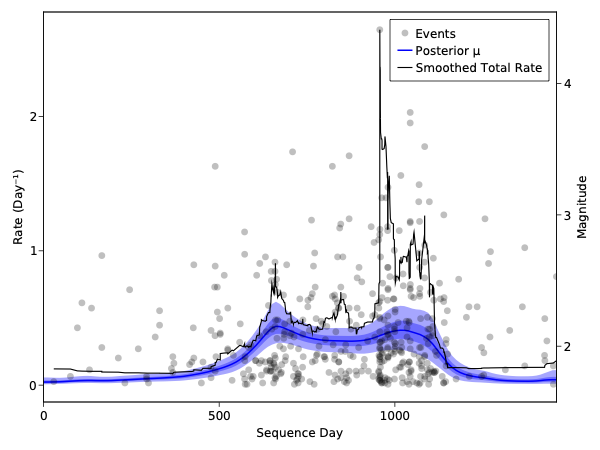

Nonparametric inference of seismicity rates using deep Gaussian processes

The occurrence of earthquakes can be modelled as a combination of background rate and self-excitation from the earthquakes themselves. The background rate depends on the local physical properties of the study area, and can tell us interesting things about stress evolution, for instance from fluid movements in the upper crust. However, extracting time-varying background rates is quite challenging! With Zach Ross at Caltech, I'm developing a flexible, multiscale and non-parametric method for studying the background rate of the epidemic-type aftershock sequence (ETAS) model using deep Gaussian processes. ETAS is a relatively well-performing empirical statistical model for seismicity, while deep Gaussian processes allow background rate effects at multiple timescales to be captured. The figure above shows the results of our methodology applied to the Cahuilla swarm in Southern California. Full details of the method may are in Muir & Ross (2023).

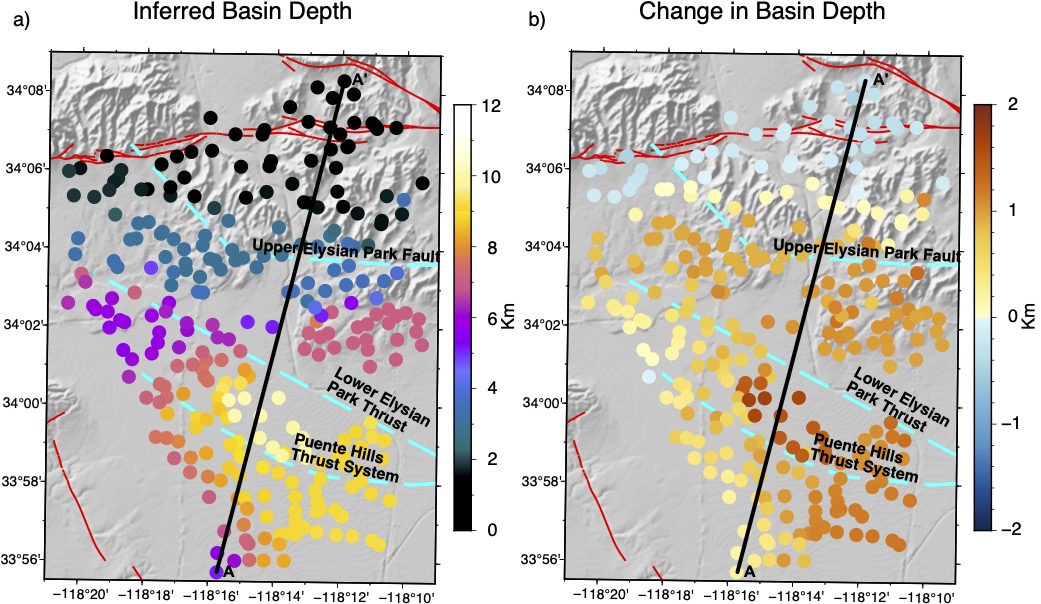

Geologically-Informed Tomography

The creation of models of Earth structure through tomographic imaging is one of the cornerstones of modern geophysics. Typically, the tomographic problem is posed using basis functions or discretizations that are mathematically expedient, rather than that reflect some underlying knowledge of the geological structures present. In Muir & Tsai (2020) we discuss an inversion strategy that implements models defined by a combination of geometric primatives (for things like faults) and more complex boundaries defined by level set functions. We then applied this methodology to image the edge structure of the Los Angeles Basin in Muir et al. (2022), using the high density Community Seismic Network deployed by Caltech. We found a steeper and deeper Northeastern edge of the basin, with significant implications for potential ground motion amplification in that area.

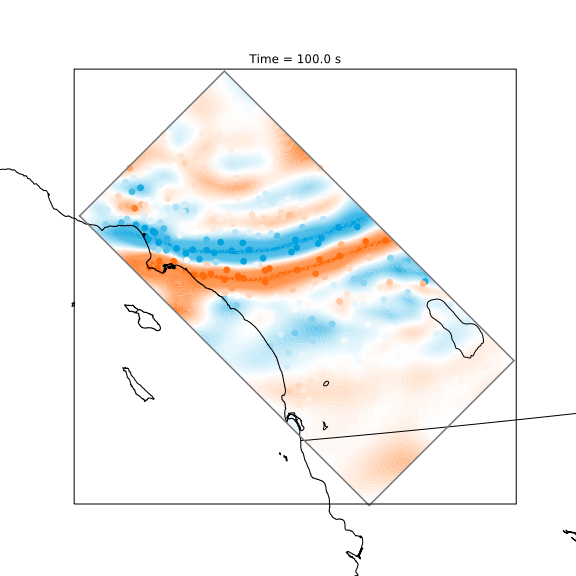

Wavefield Reconstruction for Displacement and Strain Fields

The bulk properties of the Earth are directly connected to seismic waves through the seismic wave equation, which depends on both time and spatial derivatives of the displacement. While time derivatives are now known accurately, obtaining accurate spatial derivatives is extremely difficult due to the sparse, irregular distribution of seismometers on the Earth's surface. I use a two-step wavelet-curvelet analysis with preconditioning that promotes the expected smoothness of the wavefield to optimally interpolate seismic records, allowing for better calculation of spatial derivatives of the wavefield. In Muir & Zhan (2021) we discuss this analysis in the context of the displacement wavefield, and show how it can potentially drastically lower the amount of data required for applying wavefield techniques like eikonal tomography. In Muir & Zhan (2022), we further investigate how we can use the algorithm to combine Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) and displacement sensors into a single data product.

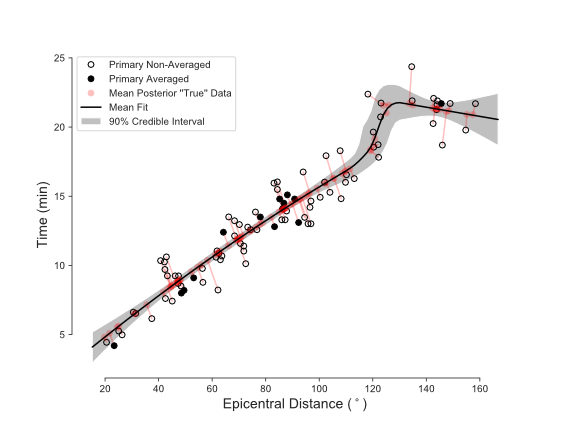

Bayesian Geophysical Methods

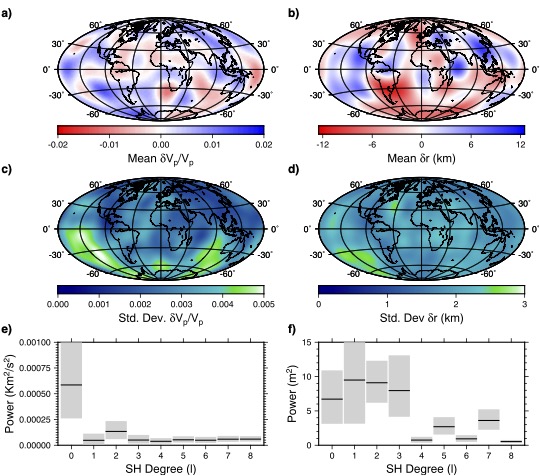

Almost all geophysical inverse problems are ill-posed, and almost all geophysical data is noisy. Solving ill-posedness requires some a priori about the likely structure of the Earth, and accounting for data requires a priori knowledge about the distribution of data errors. The Bayesian statistical framework gives us the toolset to formally account for these assumptions, with the useful outcome that we obtain some understanding of the distribution of possible solutions, rather than just the best fitting one. A recent highlight from this line of research is our finding in Muir & Tsai (2020) that the discovery of Earth's core (Oldham, 1906) is robust when only the Primary arrival dataset is included — in this study we present some useful results for handling very noisy historical datasets by marginalizing across multiple sources of error. With Hrvoje Tkalčić at the Australian National University and Satoru Tanaka of JAMSTEC, we have recently published a joint inversion of the core-mantle boundary topography (CMB) and lowermost mantle P-wave velocity using hierarchical Bayesian methods (Muir et al. 2022).

General Interest Writing

I am developing a portfolio of writing and other content aimed at a broader, non-technical audience — principally to highlight the very interesting world of solid Earth geoscience from a practitioner's perspective! The largest output of this is a collaboration with Caltech Letters, linked here — Listening to the heartbeat of our planet. I recently appeared in a podcast discussing my experiences with the John Monash foundation — The General Sir John Monash Scholars podcast featuring Jack Muir. I am also working through non-technical summaries for each of my publications, to be found linked on my publications page.